During the 1978 World Cup, two players from the Dutch team, Wim Rijsbergen and Wim Suurbier, visited Buenos Aires’ Plaza de Mayo. There, they witnessed a gathering of the mothers of Los desaparecidos, ‘the disappeared’, protesting defiantly under the eye of a military dictatorship. The desaparecidos were the thousands of students, trade unionists, and dissidents who were abducted and killed in Argentina from 1974 to 1983.

Argentina is ten times the size of the UK, and as a country with such extensive natural resources within its borders, it began the 20th century as one of the world’s richest nations. However, decades of economic downturn followed where the country alternated between periods of military juntas and precarious democracies. In 1976, a dictatorship called the ‘National Reorganization Process’ seized power, accelerating a campaign of state terrorism waged against the population which had begun during the brief presidency of Isabel Perón.

Rijsbergen and Suurbier were part of the Netherlands squad which reached the World Cup final, where they faced the tournament hosts. Argentina’s coach César Luis Menotti told his players to win the match not for the regime but for the ordinary ‘metal workers, the butchers, the bakers, the taxi drivers’ who had come to watch them play. Which they promptly did, beating the Dutch 3-1, but that didn’t stop the regime cashing in on their victory in the aftermath.

In the present day, the mothers still turn out there every week to demonstrate, and this was one of the first things that I saw in Buenos Aires when I arrived there on the eve of the 2022 World Cup. Then, as before, a World Cup was being contested amid turbulent times in Argentina: the country is facing economic catastrophe, with year-end inflation nearing 100 percent. Football remains the ultimate distraction for Argentines from these hardships, but whereas in 1978 this national passion was clearly being hijacked by the dictatorship to legitimise itself, now its importance flows solely from the people. An even greater shame, then, that the 2022 tournament was being held in a country facing its own widespread accusations of human rights abuses, but such is the stranglehold on football by the governing authorities who are supposed to protect the sport rather than debase it.

In Argentina, the World Cup was the only thing. When I walked across the border from Chile in mid-November near the mining town of Río Turbio, my hostel’s TV showed highlights of Argentina’s warm-up friendly against the UAE on a continuous loop, days after the event. The old heads of La Scaloneta buzzed around the pitch in their purple change shirts, looking like world beaters against meek opposition. And their no. 10 was being watched more intently than all the other players combined. The greatest player who ever lived, bearing the hopes of 45 million and me. Driving up further away from the border, the estancias spread out vastly on both sides of my bus, shiny rocks glinting on the ground as light passed over them. Gaucho country.

On the way to El Calafate airport where I would fly north to Buenos Aires, my cab driver keenly told me that the English just don’t have a player like Messi — no arguments from me there. He swore by young Enzo Fernandez of Benfica in the engine room of the Argentina team, a player I had only vaguely heard of. The humidity of Buenos Aires took me by surprise. I kept feeling drops from above of unknown provenance — moisture squeezed out of the saturated sky, or remnants of grey washwater from the balconies that hung over narrow pavements. I felt as though I was clawing through the air as I walked, as though through thick vegetation. Lovely jacaranda trees graced every boulevard and park, their purple blossom adorning the gnarled branches and the ground.

VUELVE LA CAMISETA QUE NUNCA SE FUE proclaimed a billboard on the outskirts of the city (‘the shirt that never left, returns’) advertising the 1986 World Cup home shirt, the one Diego Maradona wore as he skipped over the trailing legs of various opposition hatchet-men. I succumbed to one at a kiosk near the Kirchner Cultural Centre. The view on Maradona in the country was not as universally positive as I thought, though. It’s tempting to imagine him as the archetypal Argentine. But several people — hostel acquaintances, taxi drivers, walking tour guides — voiced the view that Maradona’s personal life counts against him decisively. This includes his drug use, his associations with the Neapolitan mafia, and his adultery. For some, Lionel Messi is preferred, for his loyalty to wife and family, his soft-spoken manner, the absence of obnoxious behaviour. Messi makes regular appearances on Argentinian television in adverts for things like big TVs and energy drinks. Slightly awkwardly, he insists to the viewer slogans like un futuro compartido (‘a shared future’), or una energia única en el mundo (‘an energy unique in the world’). And now, as the tournament developed, he found a new, organic catchphrase, directed at an off-camera Dutch player after the stormy quarter-final: Qué miras bobo? Anda por allá.‘What are you looking at, fool? Go over there.’

He looked like a man possessed after defeat in the opening game against Saudi Arabia, and that match quickly faded into irrelevance as the tournament progressed. I watched that game in the capital, or more accurately I watched the second half, not thinking it was worth getting up for a 7 a.m. kick-off when it seemed like it would be a walkover. I witnessed the stunning five-minute Saudi turnaround in the San Telmo neighbourhood with a group of disbelieving Argentinians. The unusually early kick-off probably tempered any overreactions from fans following the final whistle, and the mood in the city was neither overly angry nor mournful.

By the time of the Mexico game, I was in Córdoba, a large university city in the central north of the country. Following Argentina’s crucial win, a huge crowd arrived at Plaza Vélez Sarsfield, singing through megaphones, banging drums, and dancing in fountains. Having shown footage of the celebrations to UK-based friends and family, some joked that I should tell the crowds that it was only a group game they’d won. Here was one clear difference between our two football cultures – in England, no tournament victory before at least the semi-final stage would be received in this way, for fear of being made to look foolish later down the line. But in this public square, joy was being expressed in different ways by each individual, and the win signified an escape from pressures unique to each person.

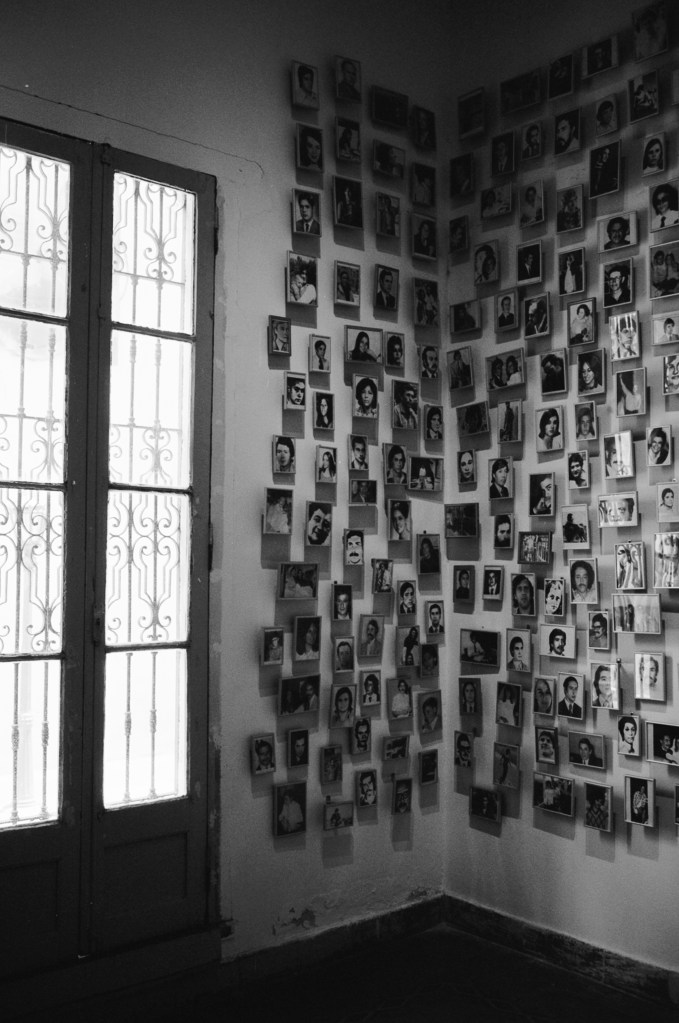

In Córdoba, as across the whole country, the sudden disappearances of the mostly young is a collective trauma which is still being processed in the national memory. The Museum of Memory plainly lists the names of those members of the special operations group at ‘D2’, the clandestine detention building which now houses the museum. Men with nicknames like ‘La Pantera’ (the Panther) and ‘Boxer’. And then there are their victims, children who they probably passed on the street, when they were simply children to these officers and nothing else, bidding them and their parents a good day. Mabel was 23 when she vanished on 10 July 1978; Monica was 25, María, 21. Here on display at the museum was what they left behind, their half-smoked cigarettes, cups of tea, dresses and jumpers left hanging in wardrobes, schoolbooks. Frozen in a glass cabinet, a diorama of innocent objects leaden with horrifying significance. Sus cortas pero intensas vidas, condensan sus deseos y luchas, sus pasiones y utopías … Their short but intense lives, condense their desires and struggles, their passions and hopes.

A simple mantra, repeated by the loved ones of the disappeared here and in countries like Chile during their dictatorship, is ¿Dónde están? (‘Where are they?’) They are not alive or dead, said military leader General Jorge Videla back then. They are Disappeared.

.

Dusty Córdoba, where the temperature hit 40 degrees, was followed by green Mendoza, where every avenue was tree-lined and bordered by distinctive deep cobbled storm drains. Here, I saw the final group game against Poland and the second-round game against Australia on a large outdoor screen on Avenida Aristides Villaneuva, jostling for view of it with thousands of others between the natural obstructions of trees, cars, and telegraph poles. Porro smoke hung thick in the air above teenagers on their summer break, cans of Quilmes, drums, backpacks facing frontwards. I would scan these blue-and-white crowds. Messi 10 Messi 10 Messi 10 (fake) Messi 10 De Paul 7 Messi 10. Rodrigo de Paul is so ‘Love Island’ that it’s uncanny – he has the exact correct number and position of tattoos, the right face, the right hair. And, hilariously, he was rubbish for the first two games, although he became a very effective midfield destroyer in later matches in this tournament, perfectly complimenting the creativity of Enzo Fernandez and Alexis Mac Allister. I shout-hummed the rousing last part of the national anthem, having not mastered the words. I had learnt a few other tunes, though:

Y ya lo ve, y ya lo ve, / ¡el que no salta, es un inglés! (If you don’t jump, you’re English!)

Anti-British sentiment is no trivial matter in Argentina – ‘English’ and ‘British’ are used interchangeably in this and many other songs – with references to the Malvinas/Falklands conflict found on signs in practically every town or village I went through, and even found in Argentina’s constitution. However, this animosity is aimed at British imperialism and should not be confused with hostility on a personal level. Not once was I made unwelcome by any of the countless people who I had conversations with in the country, even those who were particularly angry about the war.

After travelling from Mendoza to Salta in another long bus journey punctuated by traffic jams and arbitrary stops, the desire to operate on my own timetable overcame my fear of driving, so I rented a car in Salta with two other Brits. Here, as in Buenos Aires, queues snaked out of every bank all day, and cashiers would check if I wanted to pay for my grocery shopping in one upfront payment. I had learnt of the so-called ‘Coldplay dollar’ exchange rate for paying to see foreign artists perform in Argentina, one of many levies on transactions involving foreign currencies (Coldplay were inflicting ten consecutive nights of concerts upon Buenos Aires around this time). Every tariff penalising the outflow of money is ascribed its own ‘X-dollar’ name format in this way. In a half-hearted attempt to stall fears over inflation while the tournament was taking place, Argentina’s Minister of Labour said ‘First, Argentina win, then we will continue working […] one month is not going to make a big difference’.

The provinces of Salta and Jujuy lie in the north-western corner of Argentina, and the border with Bolivia and centre of the continent feels close. The patchwork multicoloured Andean Wiphala flag emerges here, flying from buildings and daubed on walls. In the town of Purmamarca, the adobe buildings seem to be carved out of the rock itself, and all around the town, rock formations in psychedelic green, blue and red hues stand side-by-side impossibly with one another. Inside our car, vapour rose from yerba mate leaves singed by the thermos water. We stopped at every viewpoint we could, taking it all in. We visited La Garganta del Diablo (‘The Devil’s Throat’), one of many in South America. Standing in it and looking all the way to the end, it was like a red amphitheatre turned on its side. Looking outward, a section of sky tore through the middle of the rising rocks as if they were paper.

Needing to sort out my route with some notice to avoid exorbitant price hikes, I had taken a chance on Brazil reaching the final, and so had planned an excursion to Rio de Janeiro. After Croatia knocked them out, I had to move this trip forward to ensure I would be in Buenos Aires for the final. This meant I sacrificed watching Argentina’s semi-final, my flight leaving for Brazil at the same time as it kicked off. The mood on the plane went from nervy to jubilant in five first-half minutes, with the pilot happily relaying the news of two quickfire Argentina goals to his passengers.

In Rio, I visited the Maracanã. In the depths of the stadium, I saw the cast footprints of the Uruguayan Alcides Ghiggia, recently deceased, scorer of the winning goal in the Maracanazo (‘Maracanã Blow’), a term used to describe the events of 1950 World Cup final between Brazil and Uruguay. Pitchside, I asked the guides which end Ghiggia scored at, but nobody there knew. The stadium, resplendent with blue and yellow seating and holding only half the capacity it once had, looks very different to the image from that 1950 final, the image. Ghiggia beginning to run away in celebration, the tired anguish on the face of the Brazilian defender as an arm rises to cover his head, the dark ball already rolling up the back of the netting, 200,000 home spectators slanting upwards from the pitch like a dark hill, silent in the background, lost in the fog of image resolution — witnesses to a disaster unfolding. Somewhere else at that same moment, a nine-year-old Pelé comforted his weeping father and made him a promise.

Back in Buenos Aires in time, I watched what was surely the greatest World Cup final of them all, at Plaza Mayor Seeber. From the 80th to the 120th minute, Kylian Mbappe put in one of the most menacing, rain-on-your-parade performances I have ever seen. The directness of his approach induced panic and caused Argentinian defenders’ motor functions to misalign. All this, having done almost nothing of note since the Poland match in the round of 16. Argentina deserved the win, and I was glad the game wasn’t settled on what seemed a very soft penalty for the game’s opening goal — the fifth by my count that they had been awarded in the tournament, ranging from marginal to scandalous (see again: Poland).

In the square where thousands came to watch it, one man was told to stop waving his huge flag because he was blocking people’s view. He obliged with a smile, waited for the complainant to walk away, then raised it again with cowardly bravado, offering out everyone and no one. In between full time and extra time I walked around the dazed square, taking pictures of the general anguish. France were right to go for the win in extra time, because there was only ever going to be one winner once it went to penalties. Two French men wildly celebrated Mbappe’s first equaliser next to me and were then very gracious to me in Spanish, assuming I was a stunned Argentina fan. Extra time was absurdly open, unprecedented for a World Cup final, making even the 2018 final seem cagey in comparison.

Having watched Messi lift the trophy at long last, thousands of us headed south to Avenida 9 de Julio where the famous Obelisk is located. On the Avenida, cars lay frozen in time abandoned by their owners, and people occupied every available flat surface like snowfall — traffic lights, bus stops, roofs, lampposts.

Y ya lo ve / ¡El que no salta es un francés!

On my final day in the city, the team were due to parade the trophy through these same streets. Four million people were there to meet them. There was a shimmer of white police helmets as a motorcade assembled on an overpass a quarter of a mile away. People drank fernet out of two-litre bottles sliced in half. The occasional mirage of a bus somewhere in the distance provoked surges forward in the crowd but it was never the real thing. A bottleneck formed behind me (I now know that this was in response to the news that the parade had been abandoned and the players evacuated) and the lamppost-people, back after a day’s normality following the game, marshalled the huge mass beneath them. Breathing space appeared and disappeared quickly. But the celebration continued, unmoved by the bad news. Clearly, the day was about much more than getting to see the gold glint of the trophy. Crowds formed in side streets where residents of the flats overhanging the street showered them with refreshing cold water. Drummers hammered out a marching rhythm, repeated infinitely, and the people sang gleefully:

Muchachos! / Ahora nos volvimos a ilusionar / Quiero ganar la tercera / Quiero ser campeón mundial!

‘Boys! / Now we get excited again / I wanna win the third / I wanna be world champion!’

These are the sights and sounds that will stay with me forever.

Rodrigo de Paul had summed it up it well after the game, standing on a pitch thousands of miles away: ‘We suffered a lot, but it feels so good. We were born to suffer, it hardens us, as we are going to suffer all our lives.’